How iFrames (Don’t) Affect SEO

July 29, 2013

The Complex Web of Personalized Search

November 10, 2013The book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini is a must-read for anyone who works in any profession designed to elicit a sale, lead or other conversion from their target audience, including and especially the business of website marketing. The focus of the book centers on identifying in the moment when compliance professionals are trying to elicit the “yes” from you and learning how to say “no.” However, it also provides valuable insights to the shortcuts that people take to make efficient, effective decisions, and how we can apply them to help our website visitors have a positive, beneficial experience with our brands.

Understanding these principles of influence can be a valuable marketing tool to convert your website’s traffic to the leads or sales that are the bread and butter of your business. When these principles are exercised in a way that is honest, ethical and not manipulative, it can create a satisfying experience for the customer that leaves a lasting feeling of trust and equal partnership. This is imperative to generate high quality leads or sales, retain customers for a greater lifetime value, and even lead them to refer friends and family to your brand.

I want to highlight the six principles of the psychology of persuasion that Cialdini outlined with a brief explanation, share some real life examples of the principles in use on the web, as well as how you can implement these principles in your own website marketing.

RECIPROCITY

People want to feel that the scales are balanced. We don’t like to feel that we owe someone a favor or a debt, and so we feel a strong urge to reciprocate. This may make us feel obligated to comply with a request from others, if we feel they have done some sort of favor or service for us. Some examples of reciprocity you may see on the web may include purchasing more from an e-commerce website if they are generous enough to offer a steep discount on their merchandise, or entering your contact information in exchange for receiving a particularly useful white paper the company has put together.

HubSpot, a robust inbound marketing software and general resource, does a fantastic job of this. They beautifully demonstrate the high value of their unique whitepaper resources, and make exactly clear what the user can expect to receive in exchange for their contact information. Then they deliver on that promise of a valuable, unique resource. Many users quickly acknowledge that they are receiving a great deal from HubSpot, and that giving an e-mail address in return is the least they can do in exchange for all they’re getting.

How can you use the Reciprocity persuasion principle in your own website marketing?

Identify the objective you’re trying to achieve with your website, and what you need from your website visitors in order to achieve that objective. Then, find out what can your brand or website provide to your visitors in return for that participation from them. What product, service or resource can you offer that will make this a mutually beneficial transaction that leaves the customer feeling like they got an honest shake, not taken advantage of? The reciprocity principle can also be used when remarketing to past customers by reminding them of the value they have received from your brand before.

COMMITMENT & CONSISTENCY

Consistency is a major shortcut people take to simplify their lives. Once we feel we have committed to something, even loosely by simply expressing interest, we feel a strong need to follow-through on those commitments. This could be because it’s easier for us to mentally and emotionally reconcile when we honor even the smallest and least concrete commitments, or because we want to project the image of being consistent. Some examples of the commitment and consistency principle on the web may include filling one quick and easy field, and then later being asked to fill out more personal information.

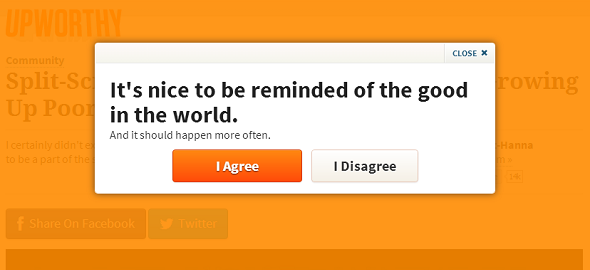

Another great example of commitment and consistency in action is Upworthy.com, a start-up dedicated to making uplifting stories go viral via social media. Many times I have clicked a link to one of their articles from an enticing Facebook share, and right as I start to read, a solitary statement pops up on screen. Sometimes it’s, “It’s nice to be reminded of the good in the world,” and other times it’s, “I support equality for all.” There are two harmless buttons to choose from: Agree or Disagree. The website user says to themselves, “Oh, of course I agree,” sees no threatening request for personal information, and clicks “I Agree” thinking it’s merely a poll they’re weighing in on. It doesn’t seem like a commitment on the surface, but it is essentially stating out loud, “This is who I am, and what I believe in.” Then Upworthy follows the pop-up with an e-mail signup form, encouraging the user to agree to receive more uplifting news from the site via e-mail marketing. Since they just committed to supporting the community’s cause, it feels inconsistent not to follow through and take that next step.

How can you use the Commitment & Consistency persuasion principle in your website marketing?

It all starts by getting even a tiny commitment from your website visitor. Just like the example above, you can ask them a question about their opinions or views that creates a verbal commitment up front. Or you can ask for one small piece of information like the user’s zip code, and deliver relevant results for them, then when they reach a form to fill out the zip code is retained along with the city and state you can automatically populate to make the form easier for them to fill out. Another way to implement Commitment & Consistency is to offer a small freebie, like requesting the user’s contact information to send them a free catalog or sample.

SOCIAL PROOF

We tend to look around us for cues as to whether lots of other people are doing something or like something, and use that information to help us make sound decisions more quickly. Much like we are more likely to tip our barista if we see their tip jar already has some money in it, or to perceive a restaurant as “good” if there is a long line to eat there, social proof is a shortcut to decision-making that suggests a product or service is good if lots of people are bought into it. This is especially true if we perceive the “lots of people” as similar to us. After all, when asked what sources influence their decisions on whether to use a particular company, brand or product, 71 percent of respondents claimed that reviews from family members or friends exert a “great deal” or “fair amount” of influence. (Harris Interactive, June, 2010) The social proof element of marketing is more prominent than ever on the web now that the use of social media has exploded.

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, in the is one of the best examples on the web of this principle. Based on the tons and tons of data they have about the pages people visit and the products they buy, Amazon is able to generate recommendations for add-ons to your order, and thus increase their average order value. For example, when browsing for Gentle Leader Collars for my two dogs, I am shown other products that are “frequently bought” with this one, and I’m told that “Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought…” On top of that, they also highlight the star rating and how many reviews exist of the product. If a product has a high rating and has tons of reviews, it seems to me that the data is more “reliable,” and I am more likely to buy.

How do you use the Social Proof persuasion principle in your website marketing?

The whole purpose of social proof is to show that people just like your customer are using and loving your product or service – so take this opportunity to brag on the nice things people are saying about your brand. Like the Amazon examples above, you can highlight ratings and reviews from real customers. You can also bring social signals to the forefront, like the number of Tweets, Facebook Likes, Google +1s and Social Shares a product or page has on the web. Brands can also use written or video testimonials and reviews. Some websites make great use of real testimonial quotes from satisfied clients on product or service pages.

LIKING

In Influence, Cialdini asserts that the likability of those who are trying to persuade us has a strong bearing on whether we comply. Whether the influencer is simply similar to us and we feel we can relate, or perhaps they compliment us on something (even trivial and unrelated), if we feel that the person is likable then we are more likely to trust them.

This obscure example may surprise you. Last week, comedian Louis CK sent out an e-mail to his distribution list promoting his latest stand-up special that is now available for download. First, Louis CK has a personal, relatable style of humor to begin with. His stand-up comedy is very much of the “we were all thinking it” variety, and his subject matter often centers around his real life as a divorced single dad of two young daughters. He already looks at the crowd and talks to us on-stage like we’re his buddies. On top of that, he wrote this personal, chatty, humorous e-mail to his fans, with typos and all. He mentions that he lost 7 pounds like you would tell a friend or family member in an e-mail, and he even signs off with, “Your friend, Louis ck.” Whether the comedian meant to do this or not, it makes us feel like by buying the download (and not leaking it elsewhere online) that we are supporting our very likable friend who took the time to write us a personal letter.

How can you use the Liking principle in your website marketing? This is all about building trust, rapport and relationships with your customers. Remember that your website visitors are not just data points in your web analytics platform. These are real people who want to be understood, connected with and respected. Listen to your customers, find the needs they have and fill them. Offer fantastic, unbeatable, personalized customer service on your website. Put real names and faces of people from your company on the website so your customers can feel connected. Above all else, ensure that your whole team is on the same page about providing enjoyable, satisfying, pleasing experiences on your website and with your brand every single time customers engage with you.

AUTHORITY

Cialdini explains in Influence how people feel an automatic sense of duty or obligation to authority figures, such as doctors in white lab coats, school teachers, or our bosses in their suits and ties. Brands often use the authority and influence of well-known and highly respected customers (think Sally Field and Boniva), or highlight quotes from industry experts when marketing their products. But it doesn’t always take a figure of authority, sometimes it can be perceived signals of authority such as uniforms, a fancy office that looks especially respectable, or highlighting special certifications or degrees.

One great example of the Authority principle in use on a website is having a photo of professional skateboarder Eric Koston front and center on the Girl Skateboards website. How is this case any different than the Liking principle, where we are easily influenced by people we like and relate to? In this case, Koston is a legitimate expert on skateboarding and all the clothing, hardware and other requirements that come with. Not to mention he’s been featured in the Tony Hawk skateboarding video game series and a handful of other skating-related video games. Because he skateboards professionally, he is an actual Authority on skateboarding, and therefore customers are more likely to trust his recommendations for a high-quality, trustworthy place to purchase skateboarding goods. So as soon as you land on the Girl Skateboards website, you’re presented with Koston’s face, wearing Girl gear of course. Shop around the site and you’re likely to see Koston again, and come across him doing a trick in a skateboarding magazine, you will be guaranteed to see him on a Girl skateboard.

How can you use the Authority persuasion principle in your website marketing?

One way is of course to use a celebrity, professional athlete or other industry authority that consumers trust to represent your brand in a positive light. Another way is to show images of people in authoritative uniforms relevant to the industry using the products. For example, a pharmaceutical website may show a doctor in a white lab coat conversing with patients. A kitchenware company may show professional chefs in action. Still another way to incorporate Authority into your marketing is to position someone at your company as a thought leader whose specialized expertise in the area is respected and even sought after. This can take a significant amount of time to create content, participate in conversations and build up a person as a thought leader in the industry, but it is often a great long-term investment for a brand over time.

SCARCITY

The final principle covered in Cialdini’s Influence is Scarcity, which suggests that products are perceived as more valuable or desirable when their availability is limited, or when we merely perceive them as scarce. Have you ever been opposite someone at a clearance clothing rack in a department store that only has 1 or 2 of an item left in a few select sizes, and feel a slight sense of urgency to snag a great piece before they get to it? If we believe that the supply of a good, service or deal is limited, or we’re told it’s the last one in stock, or if we’re told it will no longer be available after a certain deadline, we may be more likely to buy. We also see this principle in play when limited edition special releases of our favorite movies or musical artists come out. E-commerce providers like department stores benefit from this principle constantly, because clothing lines change seasonally and stock is constantly limited by size availability and when the season will swap out.

One of my favorite examples of the Scarcity principle is Groupon, the daily deal site that offers steeply discounted bargains in numerous product and service categories. Note how Groupon puts the “Limited Time Only!” exclamation and “Limited quantity available” and even an icon of a nearly empty hourglass just below the big green purchase button. It creates a feeling of scarcity and urgency to push the button and make the purchase before you lose the opportunity to. (Groupon also uses Social Proof very well by highlighting how many deals have been bought so far, plus counts of social media shares for each deal.)

How can you use the Scarcity persuasion principle in your website marketing?

This boils down to communicating a sense of urgency, or a feeling of missing out, if the consumer doesn’t act quickly. It could be a subtle statement like, “Classes are enrolling now!” as if they may not be enrolling later, or a more obvious, “Only 5 seats left in this class – enroll now!” It could be as clear cut as keeping an actively updated inventory number, so when a product you sell has only a few left in stock it gives a clear red alert to shoppers. Websites can take advantage of the Scarcity principle by clearly stating to the visitor when a certain item or service has a limited time or quantity available.

CONCLUSION

These six principles of the psychology of persuasion stand true in all aspects of marketing, and even in pitching projects at the office or making requests of family and friends. (You can pick up a copy of the book here.) They can be incredibly valuable tools to turn your traffic into real customers, but again, it is imperative that your customers feel valued, respected and treated fairly. These principles could be exploited for short term gains, but you will end up with smaller profits and unhappy customers that aren’t afraid to tell their friends, families and general public about feeling swindled. There is much more to be gained when you build relationships of trust and fairness with your customers for a greater lifetime value over time, and happy customers tell others.

What are your favorite examples of the six principles of the psychology of persuasion in action on the web? How have you used them yourself? Please share in the comments!